In abundant spare time ⏳, yours truly has implemented the non-conservative and non-dimensional form of the discretized Navier-Stokes 🍃 equations. The code 🖳 in it's simplest form is less than 50 lines including importing libraries and plotting! 😲 For validation, refer

here. More examples and free code is available

here,

here and

here. Happy codding!

The new version of the code is faster as the equations are simplified and many factors are precalculated, resulting in quicker execution times.

Code

# Copyright <2025> <FAHAD BUTT>

# Permission is hereby granted, free of charge, to any person obtaining a copy of this software and associated documentation files (the “Software”), to deal in the Software without restriction, including without limitation the rights to use, copy, modify, merge, publish, distribute, sublicense, and/or sell copies of the Software, and to permit persons to whom the Software is furnished to do so, subject to the following conditions:

# The above copyright notice and this permission notice shall be included in all copies or substantial portions of the Software.

# THE SOFTWARE IS PROVIDED “AS IS”, WITHOUT WARRANTY OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO THE WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY, FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE AND NONINFRINGEMENT. IN NO EVENT SHALL THE AUTHORS OR COPYRIGHT HOLDERS BE LIABLE FOR ANY CLAIM, DAMAGES OR OTHER LIABILITY, WHETHER IN AN ACTION OF CONTRACT, TORT OR OTHERWISE, ARISING FROM, OUT OF OR IN CONNECTION WITH THE SOFTWARE OR THE USE OR OTHER DEALINGS IN THE SOFTWARE.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

l_square = 1 # length of square

h = l_square / 500 # grid spacing

dt = 0.00002 # time step

L = 1 # domain length

D = 1 # domain depth

Nx = round(L / h) + 1 # grid points in x-axis

Ny = round(D / h) + 1 # grid points in y-axis

nu = 1 / 100 # kinematic viscosity

Uinf = 1 # free stream velocity / inlet velocity / lid velocity

cfl = dt * Uinf / h # cfl number

travel = 200 # times the disturbance travels entire length of computational domain

TT = travel * L / Uinf # total time

ns = int(TT / dt) # number of time steps

Re = round(l_square * Uinf / nu) # Reynolds number

u = np.zeros((Nx, Ny)) # x-velocity

v = np.zeros((Nx, Ny)) # y-velocity

p = np.zeros((Nx, Ny)) # pressure

for nt in range(ns): # solve 2D Navier-Stokes equations

pn = p.copy()

p[1:-1, 1:-1] = (pn[2:, 1:-1] + pn[:-2, 1:-1] + pn[1:-1, 2:] + pn[1:-1, :-2]) / 4 - h / (8 * dt) * (u[2:, 1:-1] - u[:-2, 1:-1] + v[1:-1, 2:] - v[1:-1, :-2]) # pressure

p[0, :] = p[1, :] # dp/dx = 0 at x = 0

p[-1, :] = p[-2, :] # dp/dx = 0 at x = L

p[:, 0] = p[:, 1] # dp/dy = 0 at y = 0

p[:, -1] = 0 # p = 0 at y = D

un = u.copy()

vn = v.copy()

u[1:-1, 1:-1] = (un[1:-1, 1:-1] - dt / (2 * h) * (un[1:-1, 1:-1] * (un[2:, 1:-1] - un[:-2, 1:-1]) + vn[1:-1, 1:-1] * (un[1:-1, 2:] - un[1:-1, :-2])) - dt / (2 * h) * (p[2:, 1:-1] - p[:-2, 1:-1]) + (1 / Re) * dt / h**2 * (un[2:, 1:-1] + un[:-2, 1:-1] + un[1:-1, 2:] + un[1:-1, :-2] - 4 * un[1:-1, 1:-1])) # x momentum

u[0, :] = 0 # u = 0 at x = 0

u[-1, :] = 0 # u = 0 at x = L

u[:, 0] = 0 # u = 0 at y = 0

u[:, -1] = Uinf # u = Uinf at y = D

v[1:-1, 1:-1] = (vn[1:-1, 1:-1] - dt / (2 * h) * (un[1:-1, 1:-1] * (vn[2:, 1:-1] - vn[:-2, 1:-1]) + vn[1:-1, 1:-1] * (vn[1:-1, 2:] - vn[1:-1, :-2])) - dt / (2 * h) * (p[1:-1, 2:] - p[1:-1, :-2]) + (1 / Re) * dt / h**2 * (vn[2:, 1:-1] + vn[:-2, 1:-1] + vn[1:-1, 2:] + vn[1:-1, :-2] - 4 * vn[1:-1, 1:-1])) # y momentum

v[0, :] = 0 # v = 0 at x = 0

v[-1, :] = 0 # v = 0 at x = L

v[:, 0] = 0 # v = 0 at y = 0

v[:, -1] = 0 # v = 0 at y = D

X, Y = np.meshgrid(np.linspace(0, L, Nx), np.linspace(0, D, Ny)) # spatial grid

plt.figure(dpi = 200)

plt.contourf(X, Y, v.T, 128, cmap = 'jet') # plot contours

plt.colorbar()

plt.streamplot(X, Y, u.T, v.T, color = 'black', cmap = 'jet', density = 2, linewidth = 0.5, arrowstyle='->', arrowsize = 1) # plot streamlines

plt.gca().set_aspect('equal', adjustable='box')

plt.xticks([0, L])

plt.yticks([0, D])

plt.xlabel('x [m]')

plt.ylabel('y [m]')

plt.show()

Lid-Driven Cavity

The case of lid-driven cavity in the turbulent flow regime can now be solved in reasonable amount of time. The results are shown in Fig. 1. I stopped the code while the flow is still developing as you are reading a blog and not a Q1 journal. 😆 Within Fig. 1, streamlines, v and u component of velocity and pressure are shown going from left to right and top to bottom. At the center of Fig. 1, the velocity magnitude is superimposed. As this is DNS, the smallest spatial scale resolved is ~8e-3 m [8 mm]. While, the smallest time-scale ⌛ resolved is ~8e-4 s [0.8 ms].

|

| Fig. 1, The results at Reynolds number of 10,000 |

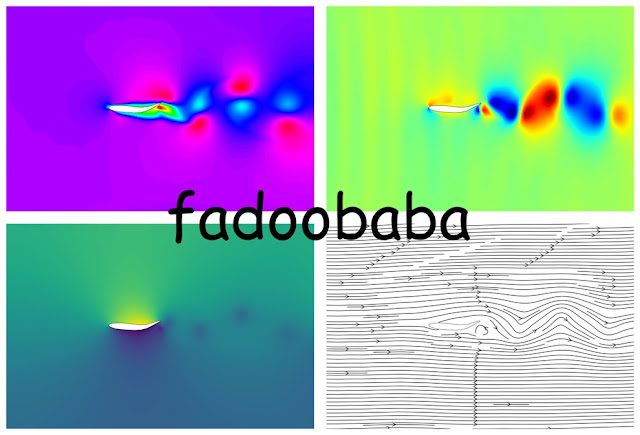

Free-Jet

The case of free jets in the turbulent flow regime can now be solved in reasonable amount of time. The results are shown in Fig. 2. I stopped the code while the flow is still developing. Once again, I remind you that you are reading a blog and not a Q1 journal. 😆 Within Fig. 2, streamlines and species are shown. As this is DNS, the smallest spatial scale resolved is ~0.02 m [2 cm]. While, the smallest time-scale ⌛ resolved is ~4e-4 s [0.4 ms]. The code for implementing species, in this case temperature using the energy equation is available on the previous

post.

|

| Fig. 2, Free jet at Reynolds number 10000 |

The benchmark case of mixed convection in an open room in the turbulent flow regime can now be solved in reasonable amount of time as well. The results are shown in Fig. 3. I stopped the code while the flow field stopped showing any changes. 😆 As this is DNS, the smallest spatial scale resolved is ~0.0144 m [1.44 cm]. While, the smallest time-scale ⌛ resolved is ~1e-4 s [1 ms]. The code for implementing species, in this case temperature using the energy equation is available on the previous

post. In the previous post, the momentum equation has no changes as the gravity vector is at 0 m/s2. For this example, Boussinesq assumption is used.

|

| Fig. 3, Flow inside a heated room at Reynolds number of 5000 |

Backward - Facing Step (BFS)

Another benchmark case of flow around a backwards facing step can now be solved in reasonable amount of time as well. The flow is fully turbulent. The results are shown in Fig. 4. I stopped the code while the flow field is still developing. 😆 As this is DNS, the smallest spatial scale resolved is ~0.01 m [1 cm]. While, the smallest time-scale ⌛ resolved is ~1e-4 s [1 ms]. As can be seen from Fig. 4, there are no abnormalities in the flow field.

|

| Fig. 4, Flow around a backwards facing step at Reynolds number of 10000 |

|

PS: I fully understand, there is no such thing as 2D turbulence 🍃. Just don't kill the vibe please 💫.

Artificial Compressibility

The artificial compressibility method is now implemented in the code. The output is flow inside the lid-driven cavity at Reynolds number 10,000. The smallest scale resolved is at 0.001 m and smallest time scale resolved is at 0.0001 s. This version of code seems to be more stable as compared to the one that uses pressure Poisson equation. The results are shown in Fig. 5.

|

| Fig. 5, Look at all those secondary vortices 😚 |

#Copyright <2025> <FAHAD BUTT>

#Permission is hereby granted, free of charge, to any person obtaining a copy of this software and associated documentation files (the “Software”), to deal in the Software without restriction, including without limitation the rights to use, copy, modify, merge, publish, distribute, sublicense, and/or sell copies of the Software, and to permit persons to whom the Software is furnished to do so, subject to the following conditions:

#The above copyright notice and this permission notice shall be included in all copies or substantial portions of the Software.

#THE SOFTWARE IS PROVIDED “AS IS”, WITHOUT WARRANTY OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO THE WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY, FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE AND NONINFRINGEMENT. IN NO EVENT SHALL THE AUTHORS OR COPYRIGHT HOLDERS BE LIABLE FOR ANY CLAIM, DAMAGES OR OTHER LIABILITY, WHETHER IN AN ACTION OF CONTRACT, TORT OR OTHERWISE, ARISING FROM, OUT OF OR IN CONNECTION WITH THE SOFTWARE OR THE USE OR OTHER DEALINGS IN THE SOFTWARE.

#%% import libraries

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

#%% define parameters

l_cr = 1 # characteristic length

h = l_cr / 1000 # grid spacing

dt = 0.0001 # time step

L = 1 # domain length

D = 1 # domain depth

Nx = round(L / h) + 1 # grid points in x-axis

Ny = round(D / h) + 1 # grid points in y-axis

nu = 1 / 10000 # kinematic viscosity

Uinf = 1 # free stream velocity / inlet velocity / lid velocity

cfl = dt * Uinf / h # cfl number

travel = 20 # times the disturbance travels entire length of computational domain

TT = travel * L / Uinf # total time

ns = int(TT / dt) # number of time steps

Re = round(l_cr * Uinf / nu) # Reynolds number

#%% intialization

u = np.zeros((Nx, Ny)) # x-velocity

v = np.zeros((Nx, Ny)) # y-velocity

p = np.zeros((Nx, Ny)) # pressure

#%% pre calculate for speed

P1 = dt / h

P2 = (2 / Re) * dt / h**2

P3 = 1 - (4 * P2)

#%% solve 2D Navier-Stokes equations

for nt in range(ns):

pn = p.copy()

p[1:-1, 1:-1] = pn[1:-1, 1:-1] - P1 * (u[2:, 1:-1] - u[:-2, 1:-1] + v[1:-1, 2:] - v[1:-1, :-2]) # pressure

p[0, :] = p[1, :] # dp/dx = 0 at x = 0

p[-1, :] = p[-2, :] # dp/dx = 0 at x = L

p[:, 0] = p[:, 1] # dp/dy = 0 at y = 0

p[:, -1] = p[:, -2] # dp/dy = 0 at y = D

un = u.copy()

vn = v.copy()

u[1:-1, 1:-1] = un[1:-1, 1:-1] * P3 - P1 * (un[1:-1, 1:-1] * (un[2:, 1:-1] - un[:-2, 1:-1]) + vn[1:-1, 1:-1] * (un[1:-1, 2:] - un[1:-1, :-2]) + p[2:, 1:-1] - p[:-2, 1:-1]) + P2 * (un[2:, 1:-1] + un[:-2, 1:-1] + un[1:-1, 2:] + un[1:-1, :-2]) # x momentum

u[0, :] = 0 # u = 0 at x = 0

u[-1, :] = 0 # u = 0 at x = L

u[:, 0] = 0 # u = 0 at y = 0

u[:, -1] = Uinf # u = Uinf at y = D

v[1:-1, 1:-1] = vn[1:-1, 1:-1] * P3 - P1 * (un[1:-1, 1:-1] * (vn[2:, 1:-1] - vn[:-2, 1:-1]) + vn[1:-1, 1:-1] * (vn[1:-1, 2:] - vn[1:-1, :-2]) + p[1:-1, 2:] - p[1:-1, :-2]) + P2 * (vn[2:, 1:-1] + vn[:-2, 1:-1] + vn[1:-1, 2:] + vn[1:-1, :-2]) # y momentum

v[0, :] = 0 # v = 0 at x = 0

v[-1, :] = 0 # v = 0 at x = L

v[:, 0] = 0 # v = 0 at y = 0

v[:, -1] = 0 # v = 0 at y = D

#%% post processing

X, Y = np.meshgrid(np.linspace(0, L, Nx), np.linspace(0, D, Ny)) # spatial grid

plt.figure(dpi = 200)

plt.contourf(X, Y, u.T, 128, cmap = 'jet') # plot contours

plt.colorbar()

plt.gca().set_aspect('equal', adjustable='box')

plt.xticks([0, L])

plt.yticks([0, D])

plt.xlabel('x [m]')

plt.ylabel('y [m]')

plt.show()

plt.figure(dpi = 200)

plt.contourf(X, Y, v.T, 128, cmap = 'jet') # plot contours

plt.colorbar()

plt.gca().set_aspect('equal', adjustable='box')

plt.xticks([0, L])

plt.yticks([0, D])

plt.xlabel('x [m]')

plt.ylabel('y [m]')

plt.show()

plt.figure(dpi = 200)

plt.contourf(X, Y, p.T, 128, cmap = 'jet') # plot contours

plt.colorbar()

plt.gca().set_aspect('equal', adjustable='box')

plt.xticks([0, L])

plt.yticks([0, D])

plt.xlabel('x [m]')

plt.ylabel('y [m]')

plt.show()

plt.figure(dpi = 200)

plt.streamplot(X, Y, u.T, v.T, color = 'black', cmap = 'jet', density = 2, linewidth = 0.5, arrowstyle='->', arrowsize = 1) # plot streamlines

plt.gca().set_aspect('equal', adjustable='box')

plt.xticks([0, L])

plt.yticks([0, D])

plt.xlabel('x [m]')

plt.ylabel('y [m]')

plt.show()

velocity_magnitude = np.sqrt(u**2 + v**2) # calculate velocity magnitude

plt.figure(dpi = 200)

plt.contourf(X, Y, velocity_magnitude.T, 128, cmap = 'plasma_r') # plot contours

plt.streamplot(X, Y, u.T, v.T, color = 'black', cmap = 'jet', density = 2, linewidth = 0.1, arrowstyle='->', arrowsize = 0.5) # plot streamlines

plt.gca().set_aspect('equal', adjustable='box')

plt.xticks([0, L])

plt.yticks([0, D])

plt.xlabel('x [m]')

plt.ylabel('y [m]')

plt.axis("off")

plt.show()

Relaxation

The relaxation parameter along with equations is now added! The "omega" parameter can be adjusted to over / under relax the simulation according to requirements! At Reynolds number of 5000, the code provides up to 4x speed in convergence with over-relaxation.

#Copyright <2025> <FAHAD BUTT>

#Permission is hereby granted, free of charge, to any person obtaining a copy of this software and associated documentation files (the “Software”), to deal in the Software without restriction, including without limitation the rights to use, copy, modify, merge, publish, distribute, sublicense, and/or sell copies of the Software, and to permit persons to whom the Software is furnished to do so, subject to the following conditions:

#The above copyright notice and this permission notice shall be included in all copies or substantial portions of the Software.

#THE SOFTWARE IS PROVIDED “AS IS”, WITHOUT WARRANTY OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO THE WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY, FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE AND NONINFRINGEMENT. IN NO EVENT SHALL THE AUTHORS OR COPYRIGHT HOLDERS BE LIABLE FOR ANY CLAIM, DAMAGES OR OTHER LIABILITY, WHETHER IN AN ACTION OF CONTRACT, TORT OR OTHERWISE, ARISING FROM, OUT OF OR IN CONNECTION WITH THE SOFTWARE OR THE USE OR OTHER DEALINGS IN THE SOFTWARE.

#%% import libraries

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

#%% define parameters

l_cr = 1 # characteristic length

h = l_cr / 600 # grid spacing

dt = 0.0001 # time step

L = 1 # domain length

D = 1 # domain depth

Nx = round(L / h) + 1 # grid points in x-axis

Ny = round(D / h) + 1 # grid points in y-axis

nu = 1 / 5000 # kinematic viscosity

Uinf = 1 # free stream velocity / inlet velocity / lid velocity

cfl = dt * Uinf / h # cfl number

travel = 5 # times the disturbance travels entire length of computational domain

TT = travel * L / Uinf # total time

ns = int(TT / dt) # number of time steps

Re = round(l_cr * Uinf / nu) # Reynolds number

#%% intialization

u = np.zeros((Nx, Ny)) # x-velocity

v = np.zeros((Nx, Ny)) # y-velocity

p = np.zeros((Nx, Ny)) # pressure

u_new = u.copy() # x-velocity (relaxation)

v_new = v.copy() # y-velocity (relaxation)

p_new = p.copy() # pressure (relaxation)

#%% pre calculate for speed

P1 = dt / h

P2 = (2 / Re) * dt / h**2

P3 = 1 - (4 * P2)

omega = 4 # relaxation parameter (omega < 5)

#%% solve 2D Navier-Stokes equations

for nt in range(ns):

pn = p.copy()

p_new[1:-1, 1:-1] = pn[1:-1, 1:-1] - P1 * (u[2:, 1:-1] - u[:-2, 1:-1] + v[1:-1, 2:] - v[1:-1, :-2]) # pressure

p[1:-1, 1:-1] = (1 - omega) * pn[1:-1, 1:-1] + omega * p_new[1:-1, 1:-1] # relaxation

p[0, :] = p[1, :] # dp/dx = 0 at x = 0

p[-1, :] = p[-2, :] # dp/dx = 0 at x = L

p[:, 0] = p[:, 1] # dp/dy = 0 at y = 0

p[:, -1] = p[:, -2] # dp/dy = 0 at y = D

un = u.copy()

vn = v.copy()

u_new[1:-1, 1:-1] = un[1:-1, 1:-1] * P3 - P1 * (un[1:-1, 1:-1] * (un[2:, 1:-1] - un[:-2, 1:-1]) + vn[1:-1, 1:-1] * (un[1:-1, 2:] - un[1:-1, :-2]) + p[2:, 1:-1] - p[:-2, 1:-1]) + P2 * (un[2:, 1:-1] + un[:-2, 1:-1] + un[1:-1, 2:] + un[1:-1, :-2]) # x momentum

u[1:-1, 1:-1] = (1 - omega) * un[1:-1, 1:-1] + omega * u_new[1:-1, 1:-1] # relaxation

u[0, :] = 0 # u = 0 at x = 0

u[-1, :] = 0 # u = 0 at x = L

u[:, 0] = 0 # u = 0 at y = 0

u[:, -1] = Uinf # u = Uinf at y = D

v_new[1:-1, 1:-1] = vn[1:-1, 1:-1] * P3 - P1 * (un[1:-1, 1:-1] * (vn[2:, 1:-1] - vn[:-2, 1:-1]) + vn[1:-1, 1:-1] * (vn[1:-1, 2:] - vn[1:-1, :-2]) + p[1:-1, 2:] - p[1:-1, :-2]) + P2 * (vn[2:, 1:-1] + vn[:-2, 1:-1] + vn[1:-1, 2:] + vn[1:-1, :-2]) # y momentum

v[1:-1, 1:-1] = (1 - omega) * vn[1:-1, 1:-1] + omega * v_new[1:-1, 1:-1] # relaxation

v[0, :] = 0 # v = 0 at x = 0

v[-1, :] = 0 # v = 0 at x = L

v[:, 0] = 0 # v = 0 at y = 0

v[:, -1] = 0 # v = 0 at y = D

#%% post processing

X, Y = np.meshgrid(np.linspace(0, L, Nx), np.linspace(0, D, Ny)) # spatial grid

plt.figure(dpi = 200)

plt.contourf(X, Y, u.T, 128, cmap = 'jet') # plot contours

plt.colorbar()

plt.gca().set_aspect('equal', adjustable='box')

plt.xticks([0, L])

plt.yticks([0, D])

plt.xlabel('x [m]')

plt.ylabel('y [m]')

plt.show()

plt.figure(dpi = 200)

plt.contourf(X, Y, v.T, 128, cmap = 'jet') # plot contours

plt.colorbar()

plt.gca().set_aspect('equal', adjustable='box')

plt.xticks([0, L])

plt.yticks([0, D])

plt.xlabel('x [m]')

plt.ylabel('y [m]')

plt.show()

plt.figure(dpi = 200)

plt.contourf(X, Y, p.T, 128, cmap = 'jet') # plot contours

plt.colorbar()

plt.gca().set_aspect('equal', adjustable='box')

plt.xticks([0, L])

plt.yticks([0, D])

plt.xlabel('x [m]')

plt.ylabel('y [m]')

plt.show()

plt.figure(dpi = 200)

plt.streamplot(X, Y, u.T, v.T, color = 'black', cmap = 'jet', density = 2, linewidth = 0.5, arrowstyle='->', arrowsize = 1) # plot streamlines

plt.gca().set_aspect('equal', adjustable='box')

plt.xticks([0, L])

plt.yticks([0, D])

plt.xlabel('x [m]')

plt.ylabel('y [m]')

plt.show()

velocity_magnitude = np.sqrt(u**2 + v**2) # calculate velocity magnitude

plt.figure(dpi = 200)

plt.contourf(X, Y, velocity_magnitude.T, 128, cmap = 'plasma_r') # plot contours

plt.streamplot(X, Y, u.T, v.T, color = 'black', cmap = 'jet', density = 2, linewidth = 0.1, arrowstyle='->', arrowsize = 0.5) # plot streamlines

plt.gca().set_aspect('equal', adjustable='box')

plt.xticks([0, L])

plt.yticks([0, D])

plt.xlabel('x [m]')

plt.ylabel('y [m]')

plt.axis("off")

plt.show()

Pre-Calculation

# Copyright <2025> <FAHAD BUTT>

# Permission is hereby granted, free of charge, to any person obtaining a copy of this software and associated documentation files (the “Software”), to deal in the Software without restriction, including without limitation the rights to use, copy, modify, merge, publish, distribute, sublicense, and/or sell copies of the Software, and to permit persons to whom the Software is furnished to do so, subject to the following conditions:

# The above copyright notice and this permission notice shall be included in all copies or substantial portions of the Software.

# THE SOFTWARE IS PROVIDED “AS IS”, WITHOUT WARRANTY OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO THE WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY, FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE AND NONINFRINGEMENT. IN NO EVENT SHALL THE AUTHORS OR COPYRIGHT HOLDERS BE LIABLE FOR ANY CLAIM, DAMAGES OR OTHER LIABILITY, WHETHER IN AN ACTION OF CONTRACT, TORT OR OTHERWISE, ARISING FROM, OUT OF OR IN CONNECTION WITH THE SOFTWARE OR THE USE OR OTHER DEALINGS IN THE SOFTWARE.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

l_cr = 1 # characteristic length

h = l_cr / 120 # grid spacing

dt = 0.0001 # time step

L = 1 # domain length

D = 1 # domain depth

Nx = round(L / h) + 1 # grid points in x-axis

Ny = round(D / h) + 1 # grid points in y-axis

nu = 1 / 100 # kinematic viscosity

Uinf = 1 # free stream velocity / inlet velocity / lid velocity

cfl = dt * Uinf / h # cfl number

travel = 10 # times the disturbance travels entire length of computational domain

TT = travel * L / Uinf # total time

ns = int(TT / dt) # number of time steps

Re = round(l_cr * Uinf / nu) # Reynolds number

u = np.zeros((Nx, Ny)) # x-velocity

v = np.zeros((Nx, Ny)) # y-velocity

p = np.zeros((Nx, Ny)) # pressure

P1 = h / (16 * dt)

P2 = (2 / Re) * dt / h**2

P3 = dt / h

P4 = 1 - (4 * P2)

for nt in range(ns):

pn = p.copy()

p[1:-1, 1:-1] = 0.25 * (pn[2:, 1:-1] + pn[:-2, 1:-1] + pn[1:-1, 2:] + pn[1:-1, :-2]) - P1 * (u[2:, 1:-1] - u[:-2, 1:-1] + v[1:-1, 2:] - v[1:-1, :-2]) # pressure

p[0, :] = p[1, :] # dp/dx = 0 at x = 0

p[-1, :] = p[-2, :] # dp/dx = 0 at x = L

p[:, 0] = p[:, 1] # dp/dy = 0 at y = 0

p[:, -1] = p[:, -2] # dp/dy = 0 at y = D

un = u.copy()

vn = v.copy()

u[1:-1, 1:-1] = un[1:-1, 1:-1] * P4 - P3 * (un[1:-1, 1:-1] * (un[2:, 1:-1] - un[:-2, 1:-1]) + vn[1:-1, 1:-1] * (un[1:-1, 2:] - un[1:-1, :-2]) + p[2:, 1:-1] - p[:-2, 1:-1]) + P2 * (un[2:, 1:-1] + un[:-2, 1:-1] + un[1:-1, 2:] + un[1:-1, :-2]) # x momentum

u[0, :] = 0 # u = 0 at x = 0

u[-1, :] = 0 # u = 0 at x = L

u[:, 0] = 0 # u = 0 at y = 0

u[:, -1] = Uinf # u = 0 at y = D

v[1:-1, 1:-1] = vn[1:-1, 1:-1] * P4 - P3 * (un[1:-1, 1:-1] * (vn[2:, 1:-1] - vn[:-2, 1:-1]) + vn[1:-1, 1:-1] * (vn[1:-1, 2:] - vn[1:-1, :-2]) + p[1:-1, 2:] - p[1:-1, :-2]) + P2 * (vn[2:, 1:-1] + vn[:-2, 1:-1] + vn[1:-1, 2:] + vn[1:-1, :-2]) # y momentum

v[0, :] = 0 # v = 0 at x = 0

v[-1, :] = 0 # v = 0 at x = L

v[:, 0] = 0 # v = 0 at y = 0

v[:, -1] = 0 # v = 0 at y = D

X, Y = np.meshgrid(np.linspace(0, L, Nx), np.linspace(0, D, Ny)) # spatial grid

plt.figure(dpi = 500)

plt.contourf(X, Y, u.T, 128, cmap = 'jet')

plt.colorbar()

plt.gca().set_aspect('equal', adjustable='box')

plt.xticks([0, L])

plt.yticks([0, D])

plt.xlabel('x [m]')

plt.ylabel('y [m]')

plt.axis('off')

plt.show()

plt.figure(dpi = 500)

plt.streamplot(X, Y, u.T, v.T, color = 'black', cmap = 'jet', density = 2, linewidth = 0.5, arrowstyle='->', arrowsize = 1) # plot streamlines

plt.gca().set_aspect('equal', adjustable = 'box')

plt.xlim([0, L])

plt.ylim([0, D])

plt.axis('off')

plt.show()

Thank you for reading! If you want to hire me as your next shinning post-doc, do let reach out!